Why Alpha Is Vanishing, and Where to Still Find It

Hands-on AI workshops with AI experts building the future of finance:

→ Identify signals nobody's tracking

→ Build dashboards to uncover insights from alt-data

Sign up for the free workshop at https://www.investmentanalyst.ai/

In this week’s report:

Why the rise of indexing is eroding active managers' stock-picking edge

High R&D firms generate an exploitable premium you can capture cheaply

Research-grounded Investor Q&A: “Do credit spreads move before equity? Can we use spread movements as a leading indicator?”

1. Why the rise of indexing is eroding active managers' stock-picking edge

Active Funds in the Era of Indexing: Performance, Timing, and Scale Effects (January 29, 2026) - Link to paper

TLDR

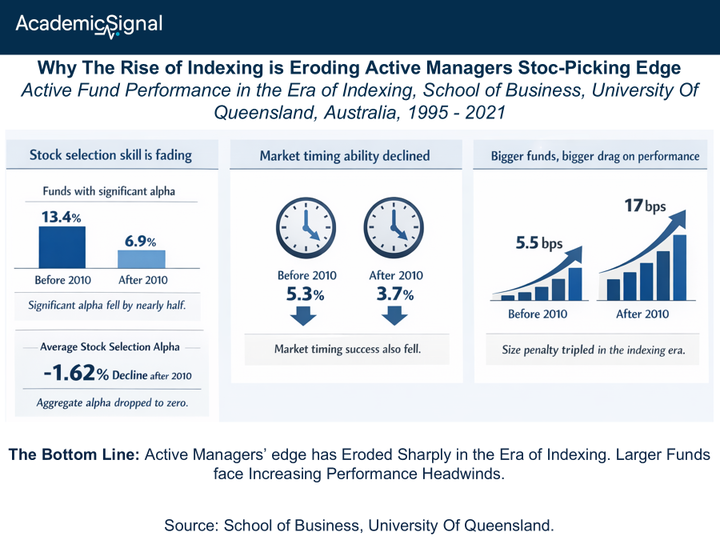

Active fund managers' stock selection skills dropped sharply after 2010, with the percentage of funds that show significant alpha falling from 13.4% to 6.9%

Market timing abilities didn't improve to compensate for the drop in stock selection skill: contrary to theory, they actually declined alongside stock selection

The performance penalty for larger fund size nearly tripled in the indexing era, from 5.5 to 17 basis points monthly performance drag every time a fund’s size doubles

The big picture

Something fundamental shifted in asset management around 2010. That's when passive fund assets – index funds and ETFs that simply track benchmarks rather than trying to beat them – began their relentless climb. By 2019, passive funds held more assets than active funds for the first time in history.

This paper asks: what happened to active managers' ability to generate returns as all this money flooded into indexing?

The answer isn't encouraging for active management.

What the authors did

Researchers at the University of Queensland assembled a comprehensive dataset of 4,419 actively managed U.S. equity mutual funds spanning 1995 to 2021. They split this sample at 2010 – the year when passive fund growth turned permanently positive and began compounding at 20%+ annually.

The study measured two distinct skills that active managers claim to possess:

Stock selection skill (alpha): The ability to pick individual stocks that outperform. If a manager consistently buys winners and avoids losers, they generate positive alpha.

Market timing ability: The ability to increase market exposure before rallies and reduce it before declines. A good market timer shifts between aggressive and defensive positioning at the right moments.

To measure these skills, the authors used two classic academic models – Treynor-Mazuy and Henriksson-Merton – that decompose fund returns into these separate components (see video walk-through).

They also examined how fund size affects performance. There's a well-documented phenomenon called "decreasing returns to scale" (DRS): as funds get larger, they tend to perform worse. The authors tested whether this penalty intensified as indexing grew. (see related paper)

What they found: stock selection is fading

Before 2010: 13.4% of funds showed statistically significant positive stock selection skill. These were managers who demonstrably picked stocks that beat the market after adjusting for risk.

After 2010: Only 6.9% of funds showed the same skill. Nearly half the proportion of skilled stock pickers disappeared.

At the aggregate level – looking at all active funds combined as a single portfolio – the numbers are even more striking.

The value-weighted portfolio generated annual stock selection alpha of 1.63% before 2010 (a statistically significant number). After 2010? The alpha dropped to essentially zero. The coefficient measuring the post-2010 change was -1.62%, completely wiping out the earlier gains.

In plain terms: the active management industry, in aggregate, stopped generating meaningful stock selection returns right as passive investing took off.

What they found: market timing didn't save the day

Here's where theory and reality diverge.

Academic models (particularly Bond and García, 2022) predicted that as more money flows into passive strategies, a tradeoff would emerge.

Index prices would become less efficient (because passive funds buy everything regardless of value), while

relative prices among individual stocks would become more efficient (because the remaining active traders would compete more intensely for fewer opportunities).

The implication: stock selection should get harder, but market timing should get easier. Active managers should pivot from picking stocks to timing the market.

The data shows the opposite.

Before 2010: 5.3% of funds demonstrated statistically significant market timing ability.

After 2010: Only 3.7% did.

Market timing got worse, not better.

Why? The authors point to institutional constraints. Mutual funds typically operate under mandates that require them to stay fully invested in equities. They can't dramatically reduce market exposure before downturns or hold large cash positions waiting for better entry points. Even if index inefficiency created timing opportunities, mutual fund managers couldn't exploit them.

This is a crucial distinction from hedge funds, which face fewer constraints and may be better positioned to capitalize on market-timing opportunities.

What they found: size hurts more than ever

The relationship between fund size and performance has always been negative: larger funds tend to underperform smaller ones, all else equal. This happens because big funds face liquidity constraints, move markets when they trade, and can't invest in their best ideas without owning too much of a company.

But the authors found this penalty has intensified dramatically.

Before 2010: Doubling a fund's size (measured by Total Net Assets, or TNA) reduced expected monthly performance by 5.5 basis points.

After 2010: The same doubling reduced performance by 17 basis points – more than 3x the penalty.

For a $10 billion fund, this is the difference between a manageable headwind and a serious structural disadvantage.

The authors also found this effect varies by investment style:

Large-cap funds actually saw their size penalty decrease after 2010, suggesting they've adapted better to the indexing environment

Mid-cap funds saw intensifying size penalties

Value funds were hit hardest, with their size-performance penalty increasing from 0.7 basis points to 4.3 basis points per size doubling

Why this is happening

The mechanism connects directly to how passive investing reshapes markets, and specifically to where alpha historically came from.

Where alpha used to come from

Active managers don't generate alpha in a vacuum. Every trade has two sides. When an active manager buys an undervalued stock and profits, someone else sold that stock too cheaply. Historically, a big source of that "other side" was unsophisticated retail investors making behavioral mistakes – panic selling during drawdowns, chasing hot stocks at the top, trading on emotion rather than analysis.

What happens when retail goes passive

When those retail investors shift their money into index funds, they stop making those mistakes. They're no longer selling individual stocks at the wrong time or buying the wrong ones at the wrong price. Instead, they're just buying the entire market, mechanically, regardless of valuation.

The pool of "dumb money" that active managers used to profit from has shrunk dramatically. The easy counterparties disappeared.

Who's left competing

Now consider who remains in the active management game. The least skilled active managers have been losing assets for years. Investors pulled money from underperformers and either went passive or moved to the remaining managers with better track records.

The active management industry has been going through a Darwinian selection process. The managers still standing are, on average, more sophisticated than the historical average.

The math of shrinking alpha

You now have fewer exploitable mispricings (because retail stopped creating them) and more concentrated skilled capital chasing what remains (because the weak hands exited).

When five skilled analysts all identify the same mispriced stock, they all try to buy it. Their collective buying pressure corrects the price faster. The window of opportunity shrinks. The alpha gets split five ways instead of going to one manager.

That's what "more efficient relative pricing" means in practice: mispricings get corrected faster because the ratio of skilled capital to exploitable opportunities has increased.

Why size compounds the problem

The size effect intensifies because larger funds need more alpha to justify their existence, but alpha opportunities are shrinking. A $500 million fund might find enough mispriced mid-caps to move the needle. A $50 billion fund cannot – the math simply doesn't work when opportunities are smaller and more crowded.

The bottom line

Active managers face a structural headwind that isn't going away. The proliferation of passive capital has compressed alpha opportunities in stock selection without opening a compensating door in market timing – at least not for mutual funds constrained by their mandates.

For allocators: This suggests heightened scrutiny of capacity. Larger funds face steeper performance decay than ever. The question isn't just "is this manager skilled?" but "can this manager's skill survive at their current asset level in an indexing-dominated world?"

For active managers: The implication is to specialize in niches untouched by indexing flows (small-caps, international markets, illiquid securities), develop genuine market timing capabilities with the flexibility to use them, or accept that the traditional stock-picking playbook produces diminishing returns at scale.

For the industry: The data supports what flows have been saying for a decade – the value proposition of traditional active management is eroding, and the burden of proof on active managers continues to rise.

2. High R&D firms generate an exploitable premium you can capture cheaply

R&D Alpha: Investment Intensity and Long-Term Stock Returns (January 23, 2026) - Link to paper

TLDR

Stocks with high R&D intensity (R&D expense divided by revenue) outperform low-R&D stocks by 3.73% annually, with a Fama-French 5-factor alpha of 4.37%

A simple top-20 R&D strategy beats the S&P 500 by 7.52% per year after costs

The effect persists within size categories, ruling out a pure small-cap explanation

The core idea

When a company spends heavily on R&D, accountants treat that spending as an expense that hits earnings immediately. But economically, R&D is an investment: it creates patents, products, and competitive advantages that pay off over years. This mismatch between accounting treatment and economic reality may cause investors to systematically undervalue R&D-intensive firms.

The paper’s author (Abhishek Sehgal) tested this hypothesis rigorously across 30 years of S&P 500 data and found a persistent, exploitable premium.

What R&D intensity measures

R&D intensity is simply R&D expense divided by revenue, expressed as a percentage. A company spending $100 million on R&D with $1 billion in revenue has 10% R&D intensity.

This ratio varies dramatically by sector. Technology and healthcare firms often run 10-30% R&D intensity. Biotech companies can exceed 100% – spending more on R&D than they generate in sales, funded by capital raises. Financials and utilities typically sit below 1%.

The wide dispersion creates meaningful separation when sorting stocks into groups.

How the study was constructed

Each July, Sehgal sorted S&P 500 stocks into five equal groups (quintiles) based on their prior fiscal year's R&D intensity. The lowest 20% of R&D spenders go into Q1; the highest 20% go into Q5. He then tracked returns for the next 12 months, from July through June.

Why July? Most U.S. companies have December fiscal year ends and file their 10-K reports by late February or March. Waiting until July guarantees all accounting data is publicly available before forming portfolios. Studies using calendar-year returns risk trading on information that wasn't yet public – a form of look-ahead bias that inflates apparent performance.

The high-minus-low R&D premium (HML_RD) is simply the Q5 return minus the Q1 return each year. A positive number means high-R&D stocks outperformed.

What the numbers show

Over 30 annual periods (July 1995 through June 2025), the premium averaged 3.73% per year. High-R&D stocks beat low-R&D stocks in 17 of 30 years – a 57% win rate. That consistency matters: the result isn't driven by a few outlier years.

The annual time-series test shows a t-statistic of 1.10, which isn't statistically significant on its own. But annual data only gives you 30 observations, which is not enough statistical power to detect moderate effects reliably.

The real evidence comes from higher-frequency tests. Monthly factor spanning regressions show a Fama-French 5-factor alpha of 4.37% per year with a t-statistic of 3.01 (p < 0.01). This means the R&D premium isn't explained by exposure to market risk, size, value, profitability, or investment factors. It's a distinct source of return.

Fama-MacBeth cross-sectional regressions – which use firm-level data each month rather than just the Q5-Q1 spread – confirm the relationship after controlling for size and book-to-market (p = 0.074).

Is it just a small-cap effect?

Many apparent anomalies disappear once you control for firm size. Not this one.

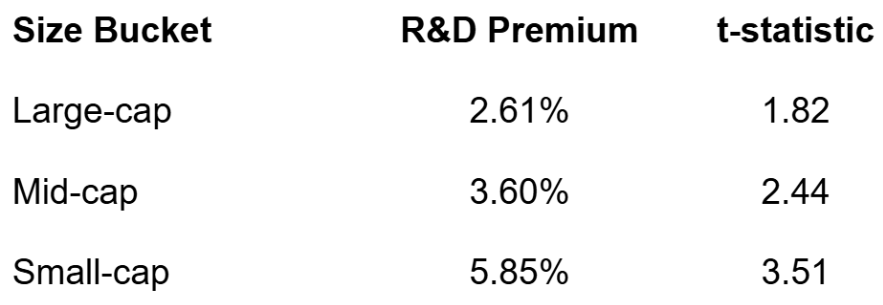

Double-sorting stocks by both size and R&D intensity reveals the premium exists across all size categories:

The premium is strongest in small caps, which aligns with mispricing explanations: stocks with less analyst coverage and harder arbitrage show larger effects. But critically, the premium remains economically meaningful even among the largest, most-followed companies.

The sector concentration reality

Here's the catch: high-R&D portfolios mechanically tilt toward technology and healthcare. When Sehgal constructed a sector-neutral version – forming quintiles within each sector, then averaging across sectors – the premium shrank to 1.04% and lost statistical significance.

This tells us roughly two-thirds of the headline premium comes from between-sector differences in R&D intensity. You're not just buying "high R&D" stocks – you're making a concentrated bet on tech and healthcare.

Whether that's a bug or a feature depends on your perspective. If you believe innovation-heavy sectors will continue outperforming, the sector tilt amplifies your thesis. If you want pure R&D exposure without sector bets, the implementable premium is smaller.

The investable strategy

Sehgal translated the signal into a simple, rules-based portfolio:

Each June, sort S&P 500 stocks by prior fiscal year R&D intensity

Select the top 20 stocks

Equal-weight them (5% each)

Hold from July through June

Repeat annually

From July 2001 through June 2025, this "RD20" strategy delivered 7.52% annual excess return versus SPY after transaction costs. The strategy's annual rebalancing generates minimal turnover, so trading costs eat only 0.027% per year.

The backtest deliberately includes stress periods: the post-dot-com crash (2001-2002) and the 2008 financial crisis. The strategy's maximum drawdown was 23.3%, less severe than the S&P 500 during the same period.

Why might this premium exist?

Two interpretations compete:

Mispricing view: Investors anchor on reported earnings, which R&D expense depresses. They undervalue firms investing heavily in future growth. As R&D projects succeed and generate cash flows, prices gradually correct upward.

Risk view: High-R&D firms face genuine risks – uncertain project outcomes, funding sensitivity during downturns, technological disruption. The premium compensates investors for bearing innovation risk.

The study can't definitively distinguish these mechanisms.

The bottom line

R&D intensity offers a persistent, cheap-to-capture signal in large-cap U.S. equities. The 4.37% five-factor alpha survives rigorous statistical tests, and a simple 20-stock strategy captures nearly all of the gross premium after costs.

The main caveats: you're making a concentrated sector bet on technology and healthcare, and the premium is smaller (though still positive) when you neutralize sector exposure. For factor-oriented investors comfortable with innovation-sector tilts, this represents a complementary return source with minimal execution drag and annual rebalancing simplicity.

3. Research-grounded Investor Q&A: “Do credit spreads move before equity? Can we use spread movements as a leading indicator?”

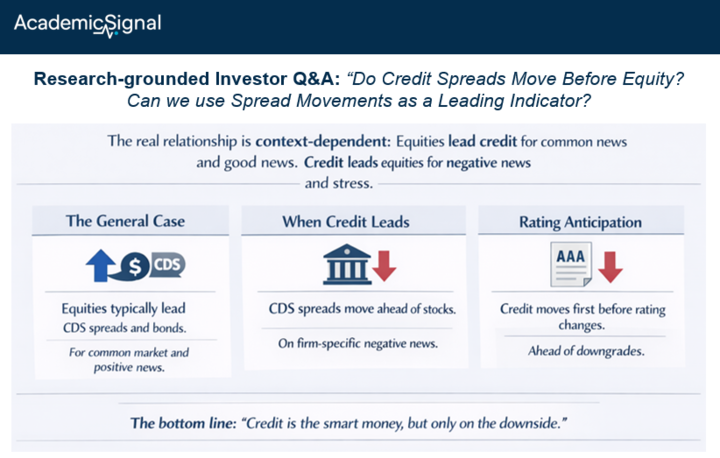

The conventional wisdom – "credit is the smart money" – is partially correct but dramatically oversimplified. The actual relationship is asymmetric and context-dependent: equities typically lead credit for common market news and good news, but credit leads equities for negative firm-specific information, rating events, and aggregate macro stress.

The General Case: Equity Leads Credit

Under normal market conditions, equities lead credit default swaps (CDS). Forte & Peña (2009) analyzed North American and European firms using a Vector Error Correction Model and found stocks lead CDS and bonds more frequently than the reverse. Marsh & Wagner (2012) confirmed this finding and added crucial nuance: the CDS lag behind equities is driven by common (not firm-specific) news and arises predominantly in response to positive equity market news.

More recent work by Procasky & Yin (2023) using time-varying coefficient VARs on 2004-2019 data confirms a two-way interactive effect: certain types of information are captured more efficiently by each market. Their methodology accounts for structural breaks that static VAR models miss, revealing that cross-market informational flow varies substantially over time.

When Credit Leads: The Insider Trading Channel

The seminal Acharya & Johnson (2007) documented significant information revelation in CDS markets consistent with insider trading by banks. Crucially, this information flow:

Occurs only for negative credit news

Increases with the number of relationship banks a firm has

Is concentrated in entities that subsequently experience adverse shocks

Why only bad news? Banks with loan exposure have material non-public information about deteriorating credit quality. When they learn their borrower is in trouble, they can hedge by buying CDS protection – in effect, shorting the firm's creditworthiness. This hedging activity by informed lenders pushes CDS spreads wider before the equity market prices in the bad news.

Recent evidence from Ismailescu, Phillips & Xu (2023) confirms this channel remains active: the CDS market plays a significant role in price formation before cross-border acquisitions, particularly when target firms are from emerging economies with greater information asymmetry and weaker governance. Information flow from CDS to equity is more pronounced when bidders have higher default risk.

When Credit Leads: The Rating Anticipation Channel

Credit markets also lead equities around discrete rating changes. Lee, Naranjo & Sirmans (2021) showed that CDS spreads move continuously in anticipation of upcoming credit rating changes, while ratings themselves adjust in slow, discrete steps. This temporal mismatch generates:

CDS return momentum of 7.1% per year (3-month formation, 1-month holding)

Cross-market spillovers from CDS to stocks generating alpha of 10.3% per year

Cross-market spillovers from CDS to bonds generating alpha of 7.3% per year

Building on this, Keshavarz & Sirmans (2024) document bond factor momentum that spills over to equity factors, with effects strongest for factors exposed to credit risk. These bond-to-stock spillovers intensify during market stress, suggesting bond markets play a unique role in processing systematic credit information.

Firm-Specific Conditions That Amplify Credit's Lead

Lee, Naranjo & Velioglu (2018) identified when CDS spreads contribute most to price discovery:

Private firms (where stocks don't trade concurrently)

Around rating events (particularly downgrades)

When firm-specific credit information is prominent vs. common market factors

The paper documents that CDS returns significantly predict stock returns – particularly the idiosyncratic components of those returns. This predictability is strongest among more liquid, informationally rich CDS contracts.

The Term Structure Signal

Beyond levels, the shape of the CDS term structure predicts equity returns. Han, Subrahmanyam & Zhou (2017) showed that a shallower credit term structure (5-year CDS spread minus 1-year CDS spread) predicts:

Decreases in default risk

Increases in future profitability

Favorable earnings surprises

Higher future stock returns (for low spread-level firms)

Lower future stock returns (for high spread-level firms)

This predictability is stronger in stocks with low institutional ownership, limited analyst coverage, and poor liquidity – consistent with slow information diffusion from credit to equity markets.

A New Mispricing Signal: The Debt-Equity Spread

Chen, Chen & Li (2023), forthcoming in the Journal of Finance, introduce the debt-equity spread (DES): the difference between actual credit spreads and equity-implied credit spreads (what credit spreads "should" be given equity market information). DES predicts:

Stock returns negatively (high DES → equity overvalued → low future returns)

Bond returns positively (high DES → bonds undervalued → high future returns)

High-DES firms are more likely to issue equity and retire debt, and have more insider equity selling, behavioral confirmation that DES captures genuine relative mispricing between the two markets. This finding supports models of partially segmented debt and equity markets.

The Aggregate Credit Signal: Excess Bond Premium

For macro timing, the most robust signal comes from Gilchrist & Zakrajšek (2012), published in the American Economic Review. They decomposed credit spreads into:

Expected default component: predicted by firm fundamentals (leverage, profitability, equity volatility)

Excess bond premium (EBP): the residual after accounting for expected defaults

The EBP drives almost all the predictive content of credit spreads. An increase in the EBP predicts:

Declines in GDP growth, industrial production, and employment over 1-4 quarters

Declines in equity prices

The interpretation: the EBP reflects the effective risk-bearing capacity of the financial sector. When intermediaries become constrained, the EBP spikes, credit supply contracts, and the real economy – and equity markets – suffer. The Federal Reserve updates this series monthly.

Practical Implementation Considerations

Negative vs. positive news: Don't expect credit to lead equities on good news. The information asymmetry runs one way.

Single-name vs. aggregate: At the single-name level, look for CDS momentum around rating-sensitive names. At the aggregate level, monitor the excess bond premium for macro turning points.

Post-crisis regulatory changes: Gadgil (2025) documents that post-2016 margin requirements have weakened single-name CDS price discovery. Single-name CDS now incorporate less information prior to rating decreases. The informational edge may have migrated toward CDS indices, which face less regulatory friction.

COVID structural break: Procasky & Yin (2023) found that COVID-19 caused a significant structural break in cross-market information flow patterns in high-yield markets, a reminder that these relationships are regime-dependent.

Liquidity matters: The credit-leads-equity effect is strongest in liquid CDS contracts. Illiquid CDS names may actually lag equities even for bad news.

The Bottom Line

Credit markets do contain leading information for equities, but in specific and predictable circumstances: negative firm-specific news (especially for firms with many bank relationships), anticipation of slow-moving rating changes, cross-border M&A with information asymmetry, and aggregate financial sector stress. The trader's adage should be refined: "Credit is the smart money, but only on the downside."

Disclaimer

This publication is for informational and educational purposes only. It is not investment, legal, tax, or accounting advice, and it is not an offer to buy or sell any security. Investing involves risk, including loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Data and opinions are based on sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness are not guaranteed. You are responsible for your own investment decisions. If you need advice for your situation, consult a qualified professional.